From his time of prominence in the 60s through the 80s to the modern imitations that dominate the horror genre, the surrealist art of Polish photographer and painter Zdzisław Beksiński has undergone a remarkable transformation. From untitled paintings to horror iconography, Beksiński’s work has clearly outlived him, but what about this work resonated with people the way it did? The story of why he made the art he made and how the generations that followed him found its meaning almost independently of his intention stands as a testament to art’s ability to come back from the dead.

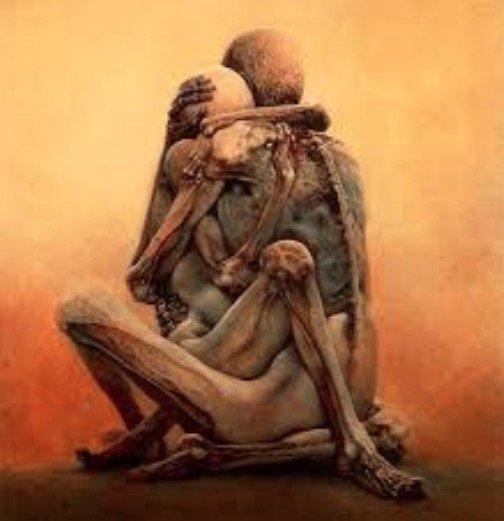

Zdzisław Beksiński was born in Sanok Poland in 1929 and was stabbed to death by an acquaintance at age 75. Before establishing himself as a painter he studied to be an architect at Krakow Polytechnic and had a brief career as a montage photographer, using complex image overlays to produce surreal and unusual images. However, Beksiński is best known for his fantastic realist painting, depicting complex and misshapen structures and people with intricate detail. Many of the figures in his paintings feature naked figures with an excess of joints and visible bone as well as stretched-thin skin and fungal decay. This appearance made much of his early audience interpret his work as–almost needlessly–dark and pessimistic, which was not out of place in communist Poland where many were still recovering from the grim images of World War II.

Though Zdzisław Beksiński would insist that he was not trying to depict morbid themes or engage in any sort of war allegory, despite the implications of his dark imagery. Beksiński professed a desire to paint “photographs of dreams”, aiming to depict images as they came to him in his mind accurately rather than trying to display a theme. In fact, his insistence upon not titling his pieces and desire to explore the subconscious put him in much the same lane as contemporary surrealist artists, but where then does this distinction find its origins? The answer may lie in Beksiński’s struggle with OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) and other private factors of his life that filled his mind with the malformed figures and decaying landscapes that filled his art.

From this background we can see the first major step Beksiński’s art took away from his intentions and toward his legacy, seemingly ready to abandon his surrealist intentions and ride the wave of postwar misery to prominence. While his art was acknowledged and praised both before and after his violent death, it was broadly excluded from the category of “fine art” on account of its deathly, erotic, and uncomfortable imagery. Beksiński’s emphasis on depicting his own mind and avoiding the overt use of allegory also meant more opportunities for audiences to label his work with their own interpretations, seemingly condemning his legacy to grim misinterpretation. However, as luck would have it, this put Beksiński’s art in just the right position for the next generation to make it their own.

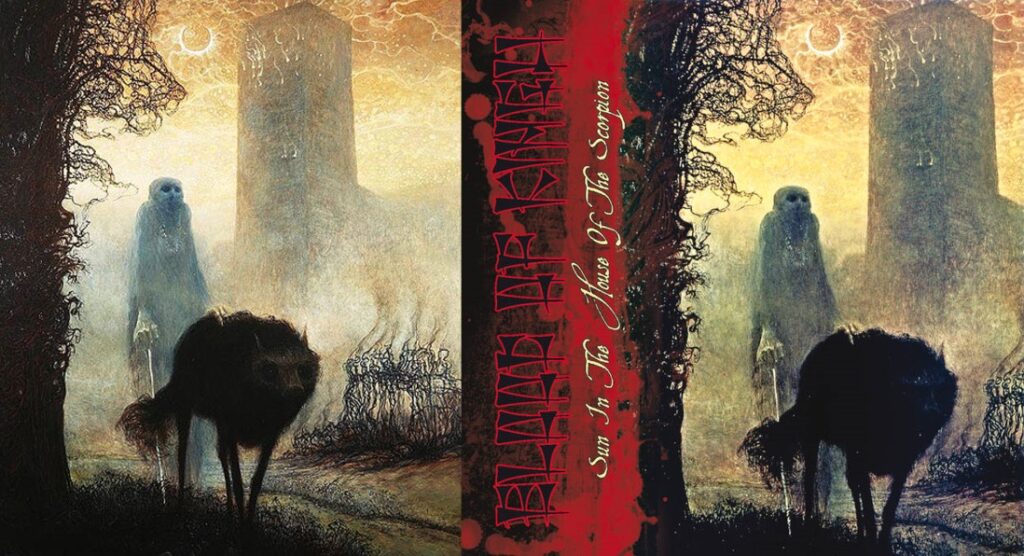

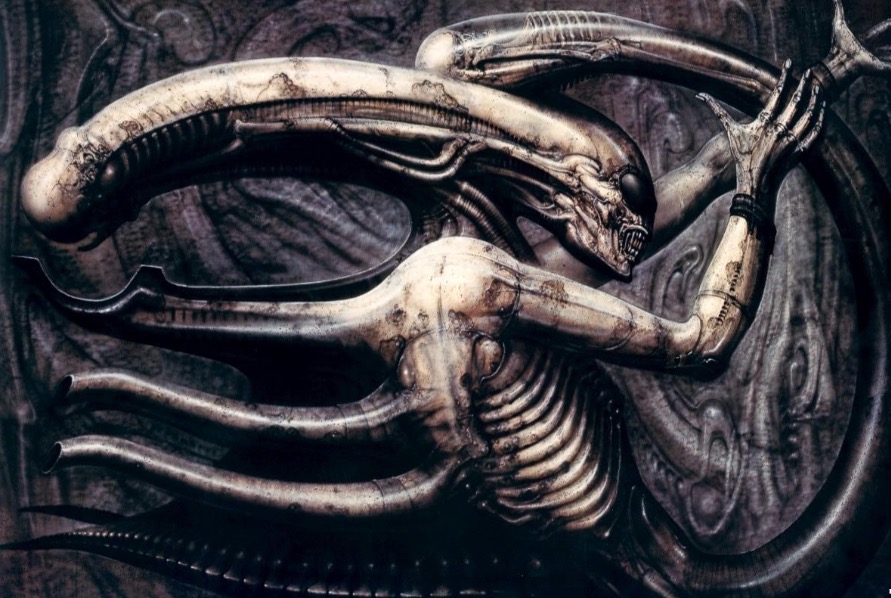

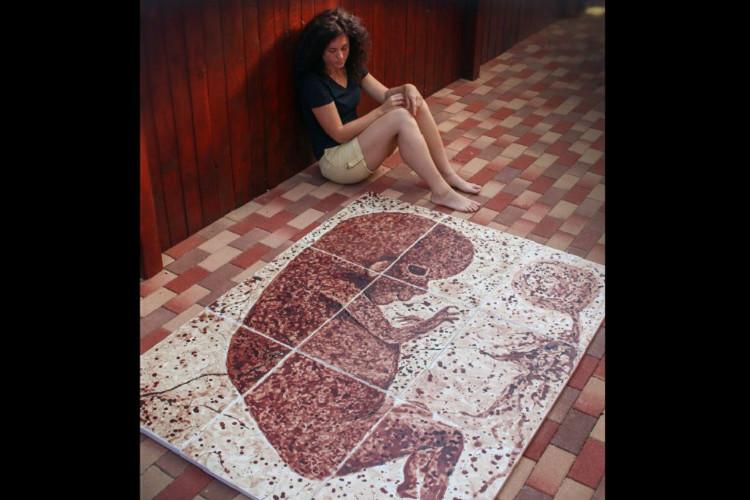

In the years immediately following his rise to prominence, horror films like Alien (1979) and metal bands like Iron Maiden (formed 1975) took inspiration from his work when making their own art. Following their success, Beksiński’s work saw even greater success across Europe and the US, securing a place in both genres going forward. Heavy metal and black metal bands of the late 2000s and early 2010s reveled in the apocalyptic imagery of Beksiński’s work and made use of it for album covers and music promotion in the years following the painter’s death. Beksiński’s dying landscapes and lone travelers, devastated by war and famine made excellent backdrops for the rage and rebellion of their music. Beksiński’s influence continues today in the enduring horror genre of films and the new generation of video games they inspired, with games like the Medium (2021) and Scorn (2022) attempting to give players the experience of interacting with the nightmare worlds Beksiński created.

Over the course of Beksiński’s posthumous success and the parallel rise of the internet, the mystery of his art’s origins and the world’s Beksiński photographed with his paints outlived their initial misinterpretation. A new generation, ignorant to the initial critiques of his work (as well as scrutiny of the emerging horror genre), are now free to learn about his art from his own accounts and make their own attempts at bringing his art to life. The uniquely grotesque style that was rejected by the fine art community managed to outlive its critics, with the exact same features that were so opposed now being the basis for all works inspired by it. Though it is impossible to know how Zdzisław Beksiński would react to his modern fame, the horrific rebirth of his aesthetic inspiring people to create new nightmares based on the art his nightmares inspired seems a poetic way to give back to the tormented artist.

I’ve never directly heard anyone name-drop Zdzisław Beksiński before. I found it quite interesting in the ways you led us through the life of the artist himself as well as the life of his artwork. It’s the classic problem that many artists face: their lives end before their artwork is recognized for its talent and message. I love the ways in which you bring up how easy it was to misinterpret Beksiński’s artwork because his intention was not understood by his audience. Eventually, his art found the people who understood it and repurposed it into their own forms of art. Heavy Metal Bands using this artwork to promote their own works really show the power of remixing and how interdisciplinary art can be. It’s incredible in the ways that the artist can die but their art can still be understood out of context. Thank you for bringing up this beautiful case study.