|

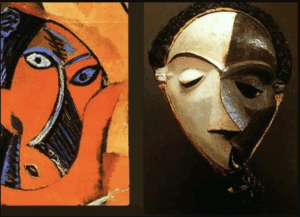

“Good artists copy, great artists steal” – Picasso (more or less) Art has always lived in the uneasy space between originality and imitation. To create is often to take, to borrow forms, gestures, and symbols that already exist in the world. Theft in this sense is less a violation than a method, although this method often creates controversy. Throughout history, the line between inspiration and appropriation blurs, and the copy becomes the crucible in which art remakes itself. In the Renaissance, copying was not scandal but training. Apprentices learned by repeating the hand of their masters, translating skill through imitation. Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin (1504) (above left) follows Pietro Perugino’s earlier altarpiece (above right) almost line for line, from the domed temple at the center to the marriage scene unfolding at its base. And yet Raphael sharpened the geometry, clarified the depth, and brought a sense of harmony that was distinctly his own. In a sense, this was a declaration of his own style and independence, with what we now consider theft as his method. By the early twentieth century, imitation no longer confirmed tradition but shattered it. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) abandoned Renaissance perspective, drawing instead on the angular geometries of African masks circulating through Paris’s colonial museums and markets. The act was generative, inspiring a worldwide movement towards Cubism, but it was also theft in a darker register. The forms Picasso borrowed were severed from their cultural origins, reimagined within an avant-garde that rarely credited their source. Innovation and appropriation were bound together, and the work’s power is inseparable from that tension.

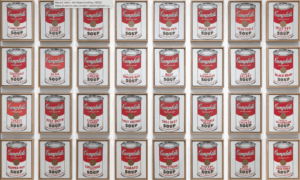

When Andy Warhol painted Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), he dispensed with the typical perception of originality altogether. Here was a supermarket label, repeated across canvas after canvas, as if the gallery itself had become an aisle. Was it theft of branding, or a mirror held up to American life? Warhol’s refusal to invent a new image became his most radical gesture. By copying what everyone already knew, he revealed how deeply repetition and consumption shape culture.

Raphael’s apprenticeship, Picasso’s rupture, Warhol’s repetition. Each marks a different inflection of theft in art. History suggests that the question is never whether artists steal, but what they do with what is taken. Copying can be homage, critique, or rupture. The distinction here is theft as method, rather than violation, though the lines are often blurred. Theft becomes art when it transforms perception, when it takes what we see and creates new reality. |

The Art World’s Open Secret: Theft

(Visited 95 times, 1 visits today)

Art world’s open secret: theft thrives in plain sight.