What comes to mind when you think of vigilante justice? Batman? What about a case of someone taking justice into their own hands when our legal systems fail to deliver it? What about before our legal systems even have a chance to deliver justice? There are numerous such cases of a person deciding for themselves that the adjudication of a court is inadequate and that therefore, they must do something–often outside the bounds of the law–to create justice where the court has failed. In some cases, people do this before the court has made a ruling. This raises many questions which I invite you to consider as I explain one such case of vigilante justice. For example, is vigilante justice necessarily wrong? What do we expect to happen when the court of public opinion agrees that the court of law has not succeeded in delivering justice? Should vigilante justice be encouraged or discouraged? Is it permissible in some cases and not in others? If so, where do we draw the line? Should we simply trust the legal system to determine what is just? Would you apply that same rule if it applied to you personally? In other words, if you deem a court’s adjudication on a matter that is important to you to be unjust, would you still hold that we should maintain our faith in the courts?

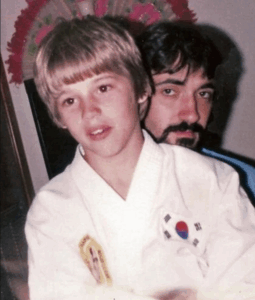

From 1983 to 1984, Joseph Boyce “Jody” Plauché was 10 and 11 years old when his parents put him in karate lessons with 25-year-old instructor Jeffrey Doucet. Unbeknownst to Jody’s parents, Doucet had been sexually abusing the young boy for at least a year. In February, 1984, Doucet kidnapped Jody, taking him to a motel in Anaheim, California, where he raped and sexually abused the boy further. Once his parents realized he was gone, Jody became the center of a nationwide missing person search, which ended after Doucet allowed Jody to call his mother from the motel. Shortly after, police raided the motel and arrested Doucet without incident. Jody was soon reunited with his parents in Louisiana. Doucet was arrested on kidnapping charges with allegations of sexual abuse and rape.

Jody’s father, Gary Plauché, reported feeling a sense of helplessness–like he had failed to protect his son. Just over two weeks after Doucet was arrested in California, he was extradited back to Louisiana to face charges. Doucet arrived at the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport around 9:30 AM where he was handcuffed and led through the airport by officers. A WBRZ news crew was waiting for Doucet to film him as he walked through the airport. As Doucet passed through the news crew filming his arrival, a man wearing sunglasses and a baseball hat turned around from a row of phone booths across from where the news crew stood. He pointed a revolver at Doucet’s head and fired a shot at point-blank range. One of the officers immediately recognized the shooter as Jody’s father, Gary Plauché, and tackled him to the ground, exclaiming “Gary, why? Why, Gary? Why?” Doucet fell to the floor and quickly bled out, dying shortly after. The entire incident was captured on video by the WBRZ news crew. You can view the footage here if you wish (VIEWER DISCRETION ADVISED!).

Gary Plauché had been informed by someone at the WBRZ news station of what time Doucet would be arriving that day and waited at the airport in a planned ambush of his son’s abuser. Plauché was initially charged with second degree murder but was offered a plea deal by the prosecution in which he pleaded no contest to the lesser offense of manslaughter. The psychiatrist that examined Plauché determined that he could not tell the difference between right and wrong at the time of the shooting. Plauché’s defense team argued that he was driven into a temporary psychotic state after learning of the abuse his son endured. Evidently, this argument worked: Judge Frank Saia ruled that sending Gary to prison would help no one and that he posed essentially no risk of re-offending. Plauché was sentenced to a seven-year suspended sentence, five years of probation, and 300 hours of community service, which he completed by 1989. Gary Plauché received no prison time for the killing of Doucet.

Some questions must now be asked: what makes it acceptable for Plauché to take justice into his own hands? Is it acceptable? And what kind of message does it send to others when a man who kills someone receives such a lenient punishment? If you have a good enough reason, are you exempt from retribution? In the case of Gary Plauché, it would seem so. Gary was hailed as a hero during and after his trial, and is still considered something of a legend in the true crime world. Maybe you think Gary’s actions were permissible and maybe not. What is clear is that Gary did not wait for the proper legal investigations and processes that were in place to seek justice. Instead, he decided that he could not wait or place his trust in the US criminal justice system, opting to play the role of judge, jury, and executioner, all at once. As a result, he was given a slap on the wrist, so to speak. Of course, it has been argued that Gary did not know right from wrong at the time of the killing. However in an interview 2 years before his death in 2014, Plauché stated that he did not regret killing Doucet and would do so again. Additionally, it would seem Gary knew what he was doing just before the shooting. He was talking on the payphone with a friend who he told, “Here he comes. You’re about to hear a shot.” Even for someone who was deemed unable to tell right from wrong, Gary received a very light sentence.

At this point, I would like to draw a parallel and a contrast between this case and another one that I wrote about previously: Andrew Brannan, a decorated Vietnam combat veteran was sentenced to death and executed for killing a police officer. Although his actions were despicable, the cause of Brannan’s undoing was clear as day. Suffering from extreme PTSD, undergoing a traumatic mental breakdown, and off his medication, Brannan killed a cop in cold blood. In that article, I argued that the reason that Brannan received no leniency was that it was all caught on camera. The dash cam footage of the shooting augmented the scenario in the minds of the jury, making it more visceral. The footage transformed what would otherwise be words read off a page into the very real and gut-wrenching cries of a young officer pleading for his life as he is shot numerous times.

Like in the case of Brannan, Plauché was caught on camera. Yet this footage seemed to have had an opposite effect than in the Brannan case. Whereas in Brannan’s case the footage buried him, the footage of Plauché killing Doucet served to call attention and support to Plauché, culminating in his glorification and lenient punishment. Thus, it seems that while the medium of film can make us despise someone, it can also do the opposite; it can make us sympathize with someone. In most criminal cases, the crime being caught on film is a key piece of evidence that virtually ensures that the perpetrator will be punished. Now there is even the phrase, “caught in 4K,” which speaks to the collective knowledge that being caught on camera doing something wrong or illegal is bad for one’s future. In the case of Gary Plauché, although he was “caught in 4K” (not literally 4K), it did not seem to matter. The public, for the most part, rallied behind him all the same.

I will leave you with some questions to consider: First, why did the medium of video kill Brannan but in some sense save (or at least not hurt) Plauché? Does video footage reveal justice or distort it? Would Plauché be forgiven if his victim was anyone other than a child predator? If you deem Plauché’s actions permissible, in what other kinds of cases could you see the killer being forgiven? How do you feel about this kind of crime being encouraged and lionized? Finally, does video footage really show the truth? Is the truth merely what occurred as it occurred? Or is it a mental construction that we viewers form on the basis of our reaction to evidence like video footage?

When questioned about why he killed Doucet, Plauché stated, “if somebody did it to your kid, you’d do it too.” Let me know your thoughts on this case and the questions it raises about vigilantism, the medium of video, justice, and criminal punishment. Thank you for reading.