Every fall, college campuses are flooded with the same familiar sight: shirts announcing fraternity rush through a parade of corporate mimicry. The Patagonia mountain becomes Delta-something. The Nike swoosh bends itself obediently into Greek letters. Coca-Cola’s script reappears, sugared down into a slogan. On campus, I’ve witnessed examples firsthand: the Ferrari logo displaying “seniors” for a fraternity, Grateful Dead’s “Stealie” now depicted with greek letters set beneath it, and many more. By now, the practice is so common that students barely register it. But viewed through another lens, it reveals a quiet art crime. The crime is in fact so banal, so culturally tolerated, that its illegality passes as tradition.

Consider the logos themselves. Though treated as mere branding, they are in fact authored artworks, designed with precision by figures like Eligio Gerosa (Ferrari) or Bob Thomas (Stealie – Grateful Dead). They occupy a peculiar position in visual culture: endlessly reproduced yet protected by law, both globally recognized and tightly controlled. When fraternities rework these designs for recruitment material, they commit a small but unmistakable breach of authorship. The practice resembles aesthetic trespassing, slipping into a professional designer’s work and rearranging its internal structure as if it were clip art.

Legally, the issue is straightforward. Unauthorized alteration of a trademarked design can constitute infringement or even dilution under the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. §1125). Most fraternities operate far below the threshold of enforcement. Their shirts circulate in small batches, printed by local vendors who know the routine and the risk. Corporate counsel do not mobilize when students wear an ersatz Coca-Cola logo to a tailgate, and so the cycle continues. The art crime persists not because it is harmless, but because it is forgettable. It hides beneath the scale of outrage.

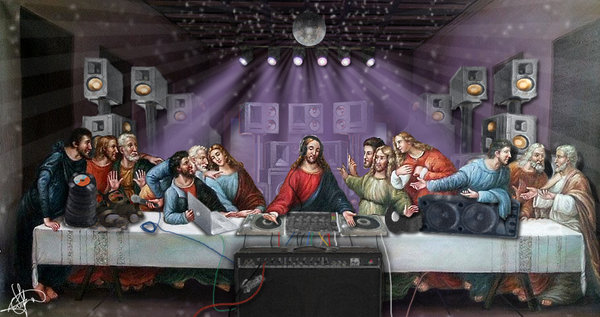

Culturally, the matter becomes more revealing. These parodies are not critiques in the Situationist sense. They do not expose ideology or undermine corporate power. Instead, they borrow visual authority to compensate for a lack of internal identity. It is an appropriation without transformation, a détournement stripped of its critical teeth. The result is a kind of counterfeit authorship, earnest and unembarrassed.

To call this vandalism of the aesthetic commons may seem dramatic, but the comparison clarifies something: the act degrades originality not through violence, but through easy substitution. Each shirt repeats the same gesture, replacing creative invention with brand cosplay. No one rush shirt is offensive. The mass of them is simply dispiriting. They reveal how thoroughly corporate aesthetics have saturated the symbolic vocabulary of campus life, to the point where designing something genuinely new feels unnecessary.

Yet this is precisely why the practice fascinates. It is an art crime that persists not through rebellion, but through indifference. The theft is casual, the alteration unexamined, the infringement practically celebratory. And because no one enforces the law, the culture adopts the violation as custom. Greek Life, then, inadvertently performs a commentary on contemporary authorship. Not the bold, declarative critique found in avant-garde practice, but an accidental one: a slow, unnoticed erosion of boundaries between art, brand, and identity. In the end, it may not be a crime of harm, but it is certainly a crime of unoriginality: one that reveals more about the state of visual culture than it intends.