Built in 1885, the Penitentiary of New Mexico is a maximum security prison holding almost eight hundred male prisoners in the state’s capital, Sante Fe. It is also home to one of the most violent and brutal prison riots in US history. What started with an officer catching two inmate drinking homemade liquor turned into a thirty-six hour ordeal that resulted in 5 officers taken hostage, thirty-three inmate deaths, and the destruction of an entire prison block.

Prisoners in the E-2 block were housed in dormitory-style barracks, with many prisoners to one room. Prisoners from Cellblock 5, notorious for their hardcore crimes, were transferred to E-2 during Cellblock 5’s renovations. The hardened criminals easily became top dogs and essentially ran E-2; even guards were reluctant to intervene in any incident that involved stepping inside. By January of 1980, prisoners began to brew liquor by fermenting old fruit and yeast. When ready, the brew was extremely potent. When inmates drank the concoction, they began to hatch a plan to fight their correctional officers. On February 2nd around 2 am, the dorm of prisoners jumped the officers in charge of final count taking five of the fourteen COs on duty hostage.

With E-2 successfully overrun, the inmates focused their attention toward Cellblock 4. This block held prisoners in protective custody: child rapists and snitches. Breaking in using blowtorches left behind by the construction crew in charge of Cellblock 5, the prisoners were hell-bent on exacting violence. Of the thirty-three deaths, twenty-four were from Cellblock 6. One inmate was decapitated and his head later was later stuck on to a broomstick. Others were castrated and forced to eat their genitalia. There was even a report of a prisoner being blowtorched until his head exploded. Most were tortured and sodomized before eventually dying at the hands of other inmates.

The culmination of these depraved acts resulted in the abandonment of the main prison facility, known as “Old Main”. Located within walking distance of the rest of the New Mexico penitentiary, it served as a daily eyesore for officers and prisoners alike. Yet for the celebration of New Mexico’s 100 year anniversary of admission to the United States, it reopened under a new guise. In 2012 Gregg Marcantel, secretary of New Mexico’s Corrections Department, devised a way for Old Main to tell its own story of the history that took place within it. He organized tours of the facility to provide context and background of the facility, particularly regarding the 1980 riot. Originally through invite only, tours conducted by people connected to the riots led tourists through the halls of E-2 and Cellblock 4. Drawing from their own experiences, these unscripted tours gave an insider’s account of the horrors that occurred. Even after the end of the centennial celebrations, the tours remained with tickets charged for admission.

By 2013, the state had hired a local television reporter to direct the entire operation. The barbershop and mess halls were reopened to the public, now staffed by current inmates held across the street at the other facilities within the prison. A gift shop was opened containing crafts made by prisoners. The formerly abandoned facility was also swept and cleaned by the currently incarcerated. Most tour guides are now reassigned correctional officers.

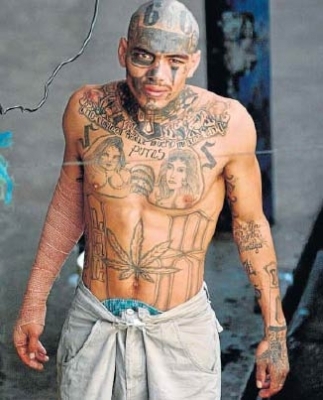

The whole concept of giving tours of a place where unimaginable horrors existed is a phenomenon known as “dark tourism”. Dark tourism is further split up into two groups: museums where the exhibits are there to educate and contextualize what took place and why, and unstructured physical sites of violence and brutality that are popular simply because something happened there. Because the tours of the New Mexico Penitentiary are basically walkthroughs of exhibits of murder and torture, the mere existence of it remains due to people’s affinity towards the raw, uncut emotions found there. Visitors do not flock there for a better understanding of prisoner treatment and prison reform. They go because people were killed, brutally murdered by deranged savages. This isn’t a Holocaust memorial or a tour of a Japanese internment camp; something that has enormous weight and gravitas behind it. The sole reason why these tours are popular is because it allows guests to experience prison.

Riots in prison are still a commonplace in today’s world, as well as police brutality and systematic oppression. In the minds of the tourists that populate the tours, they can feel that nightmare by shelling out fifteen bucks and a couple hours of the day. It isn’t to commemorate what happened, it is to revel in the lust of violence that exudes from the place.

Gone are the days where a family trip to Hawaii or San Diego feels exotic enough to call a vacation. Dark tourism is now the new way to experience life outside of your own. As a society, we collectively want to experience an escape from the boredom we feel in our everyday lives. In order to accomplish that, we put ourselves in others’ shoes. Except these shoes do not belong to the world’s one percent any more. We’re not satisfied with pretending to be people that get everything their way.

We want “real”. We want to experience life from the perspective of people lower than we are. We want to know what it is like to be abandoned. We want to feel the weight of the boot’s imprint on our face in an Orwellian dystopia. We want to experience the polar opposite of us: the dredges of society. Temporarily, society craves being depraved. We wish to escape the mediocrity of normal and understand how people can end up as murderers and psychopaths. We seek depravity, but only for a time. Because once we experience it, we want go back to being normal again. Dark tourism allows for us to feel human by witnessing the inhumane. But in the back of our minds, we all want to feel like a prisoner on a riot.

http://www.vice.com/read/getting-read-the-riot-act-0000774-v22n10