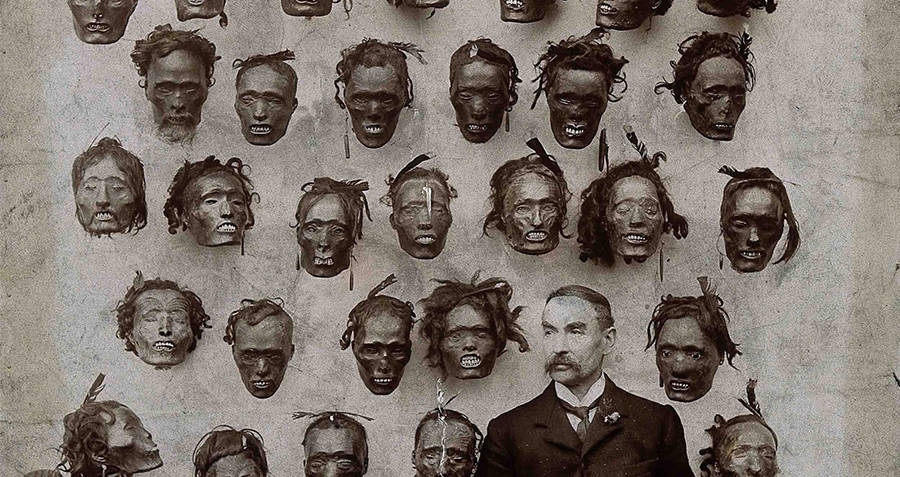

While many people go to graveyards to pay respect to their ancestors, a myriad of indigenous people have to pay respect to their ancestors in the cold alcove of a museum. Many minority groups that have been colonized lost their significant cultural artifacts to museums, and in some cases, they even lost their ancestors’ remains. This occurs more often than one would imagine because museums often keep the bones or bodies of indigenous people, e.g. the American Museum of Natural History in New York City had 30 severed heads of the Māori tribesmen.

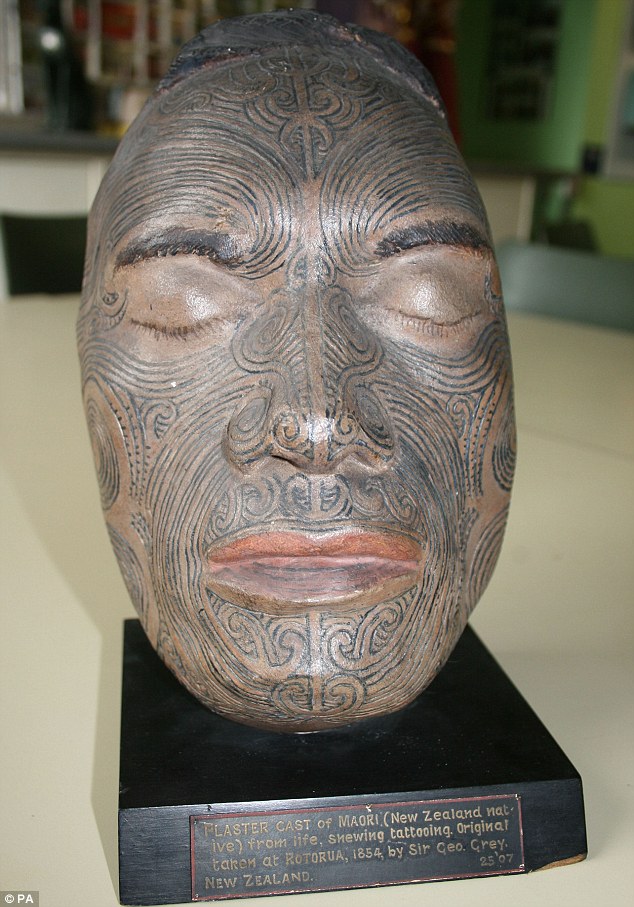

Within the culture of the Māori people, their facial tattoos were called moko and they were mainly given to high-ranking men – such as warriors or chiefs – as a symbol of status. Occasionally a woman would get a smaller moko on her chin or above her lip. After these high-ranking officials died, their tribe would honor them by preserving their heads. The process of preservation included smoking the head and drying them in the sun. Heads were referred to as toi moko and they would be given to the family of the deceased to keep and to bring to sacred ceremonies. In similar instances, heads from defeated warriors would be taken and kept as a trophy of war.

After Europeans arrived in New Zealand, the heads of the Māori tribesmen became a popular commodity to trade and sell. Europeans were fascinated by the tattooed heads, and they were traded in exchange for firearms that the Māori could use for their defenses. With new European weapons, when inter-tribal conflicts emerged, the Musket Wars began all across New Zealand. The Smithsonian Magazine stated that these wars led to an estimated 200,000 deaths, and as the need for weaponry increased, so did the selling of the toi moko. From there, the toi moko were sold to American and European museums as curiosities from across the world, and from the money, more weaponry was brought to trade for more toi moko. This need for weapons led to the Māori people tattooing and killing their slaves to gain more guns, according to the website, Art Newspaper. Although this trade was deemed illegal in 1813, it continued for a century afterwards.

In more recent times, the New Zealand government’s indigenous repatriation program has restored around 400 indigenous remains since it was established in 1990. Moreover, since 2003 the Museum of New Zealand, also referred to as Te Papa, created a unit in the museum that focuses their attention on returning the Māori skeletal remains that are held abroad. By doing so, the museum hopes to return the Māori ancestors to their descendents and to return the toi moko to their land to have a restful slumber.

The initiative the Te Papa took in retrieving these remains should be something all museums should do out of respect for the indigenous cultures that they have stolen and profited off of. Through the process of colonization and trade, many indigenous cultures lost tribal artifacts and human remains that held symbolic and religious importance. Since then, these artifacts and remains can be found in museums across the world. By keeping items that have cultural significance to indigenous people, museums do a disservice to the tribal communities. Moreover, in many indigenous tribes, it is believed that the dead cannot obtain eternal peace without being on their homelands. Keeping the remains and artifacts of indigenous groups without their permission is disrespectful to the tribes as it reveals how their ancestors are seen as a fascinating commodity and it undermines the constant suffering that is synonymous with colonization. Moreover, when considering the artifacts that museums have obtained, it is also important to reflect upon the circumstances behind their acquisition; in many cases, behind an artifact is a history of bloodshed, loss and trauma. Thus, while these exhibits can give people insight into another culture, it trivializes the experiences of the aboriginal people by making them an interesting feature in a museum while stripping them of the trials their people faced. That being said, one could argue that museums are a cultural hub, and getting rid of anything with cultural significance would lessen the cultural experience gained at a museum. While that may be true, being a conglomerate of culture, museums need to be held to certain ethical expectations, especially when concerning indigenous groups.

Various groups, such as the Aboriginal Remains Repatriation, and museums have begun the process of repatriation of indigenous remains for reburial. With these efforts, many remains of indigenous people are able to be returned to their land and their people. This process will cause museums to lose some of their popular exhibits, but nevertheless, keeping these artifacts that belong to a culture that lives on today is unjust to their tribal community and ancestors. Therefore, while there are still many remains that need to be returned to their rightful place, there have been strides made to right the disrespectful mistakes of the past.