In 1508, Pope Julius tasked Michelangelo with repainting the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo, who had made his career as a sculptor, not a painter, protested this assignment but was told in no uncertain terms that he had no choice in the matter. This interaction was seemingly enough to spark personal hatred between Michelangelo and the pope, which in addition to his preexisting issues with the methodology of the church fueled one of the most large-scale subversive artistic endeavors in history. He dedicated the following four years to the chapel’s frescoes, which span an area of over 5,000 square feet and depict a total of 343 religious figures. Ostensibly, the chapel was a massive tribute to the Catholic faith, but Michelangelo found numerous ways to express his own displeasure with the Catholic Church and the pope in small, subtle ways hidden in his paintings, many of which remained undiscovered until centuries later.

Direct criticism of religious institutions in this era was unwise; those who contradicted the fundamental beliefs of the church in any way could be labeled as heretics and receive a wide range of punishments. Such treatment was freely dispersed and far from unprecedented; even scientists like Copernicus, who made no obvious effort to directly spite the church, drew the church’s ire and were consequently killed or punished. Michelangelo had a variety of arguments with the church, but rather than risk the pope’s wrath with a direct expression of his beliefs, he concealed an array of hidden meanings in his paintings, including rude symbols directly aimed at the pope and an unusual choice of religious figures that are suspected to have alluded to the Jewish faith. He also used knowledge obtained through questionably legal means to plant secret meanings in otherwise pious images.

One of the most unambiguous subversions hidden in Michelangelo’s artwork is a painting of an angel making a rude gesture. This gesture, known as “giving the fig”, involves making a loose fist and placing the thumb between the middle and index fingers. It was considered obscene in this time period and could variably be used as an insult, to ward off evil, or to deny a request, all of which could be interpreted as a direct representation of Michelangelo’s feelings toward Pope Julius. The gesture was subtly incorporated into a painting of Prophet Zechariah, in which one of the two angels leaning over the prophet’s shoulder has a hand extended in said gesture. Not only could the inclusion of such a rude symbol in a holy artwork already be considered disgusting or blasphemous, but Michelangelo situated this painting directly above the pope’s seat in order to make it perfectly clear who his ire was directed towards. The gesture appears again in Michelangelo’s painting of the Cumean Sibyl, which is not as pointedly placed but nonetheless makes it clear that the symbol is no coincidence.

Additionally, Michelangelo’s artwork included religious themes that were generally assumed to be in line with the beliefs of the Catholic Church, but which have more recently fallen into question. First and foremost, he decorated the Sistine Chapel primarily with figures from the Old Testament. This in itself does not necessarily indicate any subversive messages, but out of the 343 figures he included, very few are from more recent Biblical canon, which may have been a subtle suggestion that Michelangelo believed the church needed to return to its roots. It is now widely believed that he held strong opinions about corruption in the church, and these beliefs are thought to be reflected in his art.

Michelangelo had an unusually expansive education for his time period; he was an apprentice to Domenico Ghirlandiao, a prominent Renaissance artist, in his youth, then went on to study at the highly prestigious Humanist Academy in Florence. His studies exposed him to a wide and fairly uncommon range of topics, one of which is now thought to be Judaism and the Kabbalah. These studies left him with a strong opinion that the Catholic Church needed to acknowledge its roots in the Jewish faith, especially given that he painted his frescoes in a time period where Jewish sacred texts were being burned and the Spanish Inquisition was at its peak. The Catholic vendetta against practicing other faiths was so strong at this time that a discovery that Michelangelo had represented traditionally Jewish figures in a Catholic stronghold would almost certainly have resulted in a death sentence.

Fortunately, Michelangelo’s deceptions did not come to light until many centuries later, when a restoration to some paintings in the chapel led to the discovery that a number of figures wore clothes adorned with a yellow circle on the sleeve. Like the Stars of David that were used to mark Jews during the Holocaust, these circles identified Jews during the reign of the Catholic Church’s Fourth Lateran Council, an organization devoted to reclaiming the holy land and reforming the church in 1215. One of the figures marked with a yellow circle was Aminidab, who is believed to be an ancestor of Christ and therefore a central figure. Though exact motives are unknown, historians and art scholars believe this to be a condemnation of the church’s treatment of the Jewish faith. Other academics believe these to be extended jokes that Michelangelo left for himself, but regardless of his actual intent, any one of these symbols could easily have had him marked as a heretic or killed.

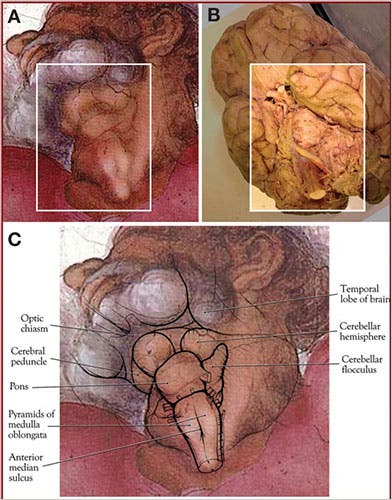

The hidden meanings and symbols concealed in Michelangelo’s frescoes are not purely vindictive or religious. The secular symbology in the Sistine Chapel, though not directed at any specific figures or suggestive of heretical beliefs, is no less criminal. In addition to his studies about philosophy, sculpture, and religion, Michelangelo was able to obtain special permission to perform dissections on corpses from a hospital, a practice which was entirely forbidden by the church at the time. These practices refined his understanding of human anatomy, which contributed greatly to his lifelike marble sculptures as well as his inclusion of lesser-known human anatomy in the frescoes of the chapel. In fact, one of his most famous portions of the chapel, the Creation of Adam, is believed to have been directly influenced by Michelangelo’s studies of the human form; the shape of the drapery in which God appears to Adam is remarkably similar to that of a human brain. This connection has a vast array of metaphorical implications. It can be assumed that Michelangelo’s associations between God and the human brain indicate his views on the fundamentally divine nature of the human form, even if his methods of expressing these beliefs may have been frowned down on by the church. As with the inclusion of the “fig” gesture, however, the shape of the brain appears to be no coincidence. A cranial shape is also visible in the unusual shape of God’s neck and torso in The Separation of Light from Darkness, which modern neurosurgeons have claimed bears a strong resemblance to the brain stem and even a spinal column. Ultimately, there may well be countless more unknown symbols concealed in the Sistine Chapel or paintings like Michelangelo’s which have not yet been discovered or simply lost their meaning over time. Expression was limited for artists who wanted to avoid suspicion from the church, and secret symbology was a relatively easy way to insert one’s own opinions into otherwise innocuous works.

This article is extremely thorough and well organized. I enjoyed reading this, especially considering I just spent a few months studying in Italy. I was privileged enough to visit the Sistine Chapel, and in hindsight, it would’ve been really interesting to search for the concealed elements you have discussed here. I enjoyed your detail in laying out the narrative of the relationship between Michelangelo and the Catholic church, with specific callouts to nuances that contributed to the overall interpretation of his hidden messages.