Photographs taken by killers are perhaps the most unsettling form of true crime memorabilia. Unlike forensic or journalistic images, these photos were often created with intent– the killer consciously framed, staged, or captured the victim in ways that reveal their own psychology. In doing so, they transform the act of murder into a kind of horrific authorship. These images can be considered “art” not because they are beautiful and admirable, but because they bear the hallmarks of artistic creation: deliberate composition, aesthetic choices, and symbolic meaning. Some killers photographed their victims as trophies, arranging them in specific poses. Others documented the process of violence itself. These photographs are not just random snapshots; they are visual narratives crafted by perpetrators, testaments to their control over life and death. The fact that the “artist” is also the murderer makes them fundamentally different from other forms of violent art. They cannot be separated from their criminal origins. Each photo is both a piece of evidence and an extension of the crime itself, the killer’s attempt to immortalize their power and aestheticize their violence. This duality is precisely what makes them objects of fascination in the world of true crime memorabilia. They are at once art and crime, creation and destruction, aesthetic object and moral abomination.

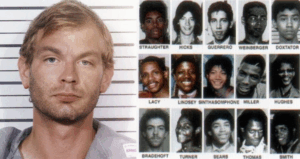

Many infamous killers blurred the line between crime and art by creating or keeping disturbing forms of memorabilia. Jeffrey Dahmer notoriously took Polaroid photographs of his victims, arranging bodies like grotesque still lifes. Dennis Rader, the BTK killer, staged self-portraits in his victims’ clothing and poses, turning his crimes into twisted performances. Rodney Alcala lured women under the guise of a photography session, leaving behind hundreds of haunting images. And these are only a few, most popular examples. Countless other killers have left behind similarly macabre artifacts, each transforming violence into a dark visual record.

Jeffrey Dahmer’s crimes in the late 1980s and early 1990s shocked the world for their brutality and the chilling artifacts he left behind. Among the remains of 11 victims, police also found around 85 petrifying Polaroids. Dozens of photographs showed his victims at different stages of his murderous process: alive, drugged, dismembered, and set up in macabre poses. For Dahmer, the photos were trophies and memory aids. But looked at from the outside, they are horrifying “still-lifes”, each one arranged with a twisted attention to composition. The polaroids have become infamous not just as evidence, but as dark cultural objects. Reproductions have circulated online, in documentaries, and even as references in art. In their grotesque staging, they highlight how Dahmer’s desire to preserve and possess also created something resembling visual art, though born of unimaginable violence.

Dennis Rader, known as the BTK (blind, torture, kill) killer, also turned to photography as part of his ritual. After murdering victims, Rader would sometimes dress in women’s clothing taken from the victims, then stage elaborate self-portraits. He used tripods and timers to capture himself bound and gagged in positions mimicking those he forced upon others. These photographs are both crime and performance art. They reveal Rader’s obsession with control, identity, and ritual – but also a disturbing sense of self-expression. The theatricality of his images makes them resemble avant-garde performance pieces, except that their meaning cannot be separated from the reality of the murders. As memorabilia, they illustrate how a killer’s inner world can be externalized through art-like practices, even if their purpose was deeply criminal.

Rodney Alcala, later dubbed the “Dating Game Killer,” used photography as his lure. He approached women and children with the persona of a professional photographer, convincing them to model for him. After his arrest, authorities found a cache of over a thousand photos of believed victims. Some of these were candid and others carefully posed, capturing his victims and other unidentified women. Alcala’s images are haunting because, on the surface, they look like ordinary portrait photography, echoing the conventions of fashion and art photography of the late 1970s. Yet beneath the surface lies manipulation, coercion, and in some cases death. His portfolio reveals the thin line between art and predation: the camera became a tool of creation and a weapon of control. Even today, the release of his photographs has sparked investigative leads and ethical debates about whether these images can or should be exhibited.

True crime memorabilia forces us to confront uncomfortable questions. When does an object of violence become art? Should such items be preserved, collected, or displayed? The photographs of killers like Dahmer, Rader, and Alcala remind us that crime and art can be entangled in disturbing ways. They are records of deaths, but also works of creation—unwilling collaborations between a perpetrator and the victim. To look at them is to face both our cultural fascination with crime and our own uneasy attraction to the aesthetics of darkness.