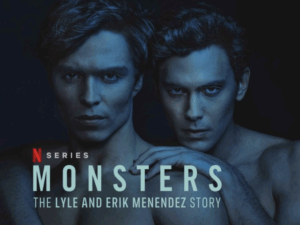

It’s no new fad that people are intrigued by true crime and gruesome stories. We all know the cult classics such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Psycho, The Shining, and The Exorcist that have captured the attention of horror fanatics for decades. But what happens when the story becomes real? Do the bone chilling tales pack the same punch when the real perpetrators and victims are out in the world today? We all know the far too familiar feeling that sinks deep into your stomach when the words “based on a true story” appear on the screen of a 2-hour thriller. But what if it’s no longer just based on a true story, what if it involves the actual livelihood of real people? In September 2024, American writer, director, and producer Ryan Murphy explored just that with season 2 of his hit biographical crime drama “Monster: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story”.

Following one of America’s most infamous family murder cases, the 9-episode season explored the 1989 murder of José and Kitty Menéndez in their Los Angeles home, with their two sons Lyle and Erik Menéndez as the central suspects. Murphy’s series dissected this controversial trial that had much of America in its grips in the early 1990s, and tackled the question of: did they really do it? Murphy’s depiction of the Menendez brothers offered enthralling courtroom drama and new shocking family secrets that brought the question of their motive to the forefront.

But while the television series was engulfed with success and praise from 11 Emmy Award nominations (including 1 win for Outstanding Picture Editing) and 3 Golden Globe nominations in the following awards season, it was also heavily criticized due to its depiction of the real story. Murphy received heavy criticism in regard to his portrayal of the brothers. Many deemed that it glorified a horrible and traumatic case and pushed the brothers into a particular role, meanwhile the actual case was much more nuanced and complex. Soon after the premier of the series the brothers themselves, who at the time were facing life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for first-degree murder, called Monsters a “phobic, gross, anachronistic, serial episodic nightmare” and “riddled with mistruths and outright falsehoods”. The family along with many critics worried that Murphy blurred the line between fact and fiction too far with his romanticized version of their story. Murphy’s twisted tale explored many possibilities of a motive for the brothers and even touched upon speculation of a possible incestuous relationship between the two, a relationship which has not been proven to be true in any court of law.

While there were many criticisms of the series, many also spoke out to support Murphy’s work and establish his right to creative freedom. Actress Leslie Grossman, who played a supporting role as Judalon Smyth within the series, came forward with her own opinion on the matter. “They’re making a painting, not a documentary,” Grossman told PEOPLE. An opinion that proved to be exceedingly popular with those that enjoyed Murphy’s adaptation. But while we can appreciate the art that is television, we must also ask ourselves whether it is truly ethical to make it out of other people’s pain. Especially so when these people are still dealing with the effects of the real story to this day.

Murphy’s previous season in this series, Dahmer, raised similar concerns about the ethicality of true crime television. While it did successfully entertain audiences and garner similar award worthy attention, according to some the Dahmer series wandered slightly too far into a romanticized version of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. The Dahmer series also faced backlash from friends and families of the killer’s victims.

True crime dramatizations have the ability to reignite public debate about cold cases, injustice, and systemic failures. Such that we can see how the public became invested in the Menendez brothers’ recent eligibility for parole, and the public’s growing interest in how survivors of sexual abuse are treated in court. But it is a slippery slope between glossy productions for attention value and a true emphasis on justice. Where do we draw the lines between art, advocacy, and glamorization?

While there is no straightforward answer to this question, we should continue to ask ourselves whether fulfilling our own morbid curiosities is worth exploiting others’ pain. We live in an era where the line between entertainment and news is already dangerously thin and if true crime dramas are here to stay, we must choose how we can responsibly tell these stories.

I like how this article ultimately focuses on how we can address the problem. Today, society has few restrictions on the subject matter of film and television, a testament to the artistic growth of film and television. However, this also indirectly raises many ethical questions, such as the article’s discussion of whether true-life adaptations can cause secondary harm to the victims’ families. However, I believe there’s still some way to go in finding a balance between entertainment and morality.