In 200 C.E., a painted wooden portrait from Egypt depicted the members of the Severan Dynasty: Emperor Septimius Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and their two sons, Geta and Caracalla. Adorned in gold and jewels, the family appeared united and powerful. In reality, this was far from the truth. If you look closely at the image, you’ll notice that one face, that of Geta, is violently scratched out. This was not an accident… It was a way of rewriting history, and creating a new legacy, which is a strategy that has been adapted modernly by many authoritarian regimes to control their citizens and the perceptions of other nations.

This is one example of a process that was common in Rome: Damnatio memoriae. Translating to “your memory is damned”, the term is used to categorize the act in which the Roman government would condemn the memory of a person who was seen as a tyrant, traitor, or enemy of the state. Within this process, any images or sculptures of these individuals would be destroyed, their names would be erased from inscriptions, coins with their face would be recalled, and any laws they made would be rescinded. To erase someone’s face was to deny their existence, to claim ownership over how their history was to be told.

So why was Geta erased from Roman history? To find the reason, we have to look back at the brothers’ rise to power. Following their fathers death, both Caracalla and Geta were expected to share power and be dual-emperors of Rome. However, this stable and unified imperial family image that their father pushed out to the citizens of Rome during his reign was far from the truth. In reality, the brothers despised each other, with the court even being divided between factions based on which brother held their loyalty. The pair divided everything, from the palace rooms to political meetings… and even had plans to geographically split the empire. Tensions continued to rise, and in 211 C.E., Caracalla lured Geta to their mothers private chambers for what was said to be a “peace meeting”. But what happened instead was the brutal murder of Geta. Surrounded by guards, Caracalla stabbed his brother to death, with ancient sources claiming that Geta clung to their mother, begging for protection. This marked the end of their fathers desired vision for the empire, and was the beginning to a chilling act of political and societal erasure that would plague Caracalla’s reign.

Caracalla ordered a damnatio memoriae against Geta, having his name scratched from inscriptions, his portraits carved away or destroyed, and his memory being condemned. However, Caracalla didn’t stop there, as he began executing Geta’s friends, allies, and supporters. In the end, ancient sources claim that almost 20,000 people were killed. Caracalla’s message was clear, both at the time and centuries later… loyalty to his brother, even remembering his name, would come with consequences. This became a defining characteristic of his reign, revealing his immense brutality.

In response, Caracalla would build monumental sculptures and architecture in order to create a facade that he was in control of Rome, even though he was plagued with paranoia following his murder spree. The Baths of Caracalla (216 C.E.) are a primary example of this. Despite this project being started by his father, Caracalla completes it and claims the whole process as his own. Roman baths were very popular with the people, not just for people to clean themselves, but for them to socialize. Scholars often coin them as “palaces for the poor”. With it being foundational for citizens’ everyday lives, Caracalla constructed this to please the people and regain popularity. The baths had four entrances and could accommodate 16,000 people at a time… everything from a normal bath house was doubled. In its interior, there were forty statues (that have been recovered) of Caracalla. In said sculptures, he was depicted as mythological figures like Hercules and Neptune. In short, these baths were one big propaganda piece to win over the people, and to subtly spread the idea that he is a strong and supportive leader.

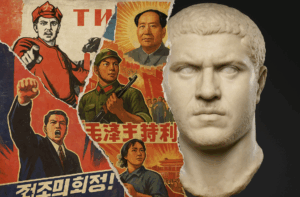

Despite this practice being centuries old, dictators modernly can be seen to use these strategies to not only control how their citizens perceive them, but how the outside world does. In North Korea, for example, perceptions and imagery that is seen of the nation are frequently controlled and manipulated. Kijong-dong (“Peace Village”) is located across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), placed in a way that it is visible from South Korean military posts. The town appears to be well-kept, with high rises and farmlands. However, many speculate that this is a facade, pointing out painted-on windows and fake buildings with no interior floors or lights. There are also loudspeakers that constantly blare propaganda and patriotic music. The point of this city is to lure South Koreans to come to North Korea by giving them the impression that North Korea is thriving, when in reality it is failing. Also, when North Korea attended the 2018 Olympics, they were incredibly controlling over the media and what was published in order to control the perception of their leader and their nation.

This raises the question: how much can we trust art when studying the history of nations? The Romans were able to completely eradicate evidence of emperors they deemed traitors, which as we can see by Caracalla and Geta, was often a biased process. So much of history is lost because of this, and as a result, our knowledge of what truly occurred in the past is incomplete. Emperors were also able to manipulate their people through the construction of luxurious facilities, almost to bribe them for their loyalty. If nations like North Korea can do this modernly, how does this impact our perception and how much of what we know, and of what North Koreans know, be limited? Art can be so easily manipulated into a propagandistic tool, so much so that it even impacts our perception of history.