On October 19th, 2025, a four-person crew disguised as maintenance workers broke into the Louvre Museum in Paris, accessed the Galerie d’Apollon, and made off with eight priceless pieces of the French Crown Jewels in just seven minutes. The robbery, executed with precision and silence, reignited global fascination with the nexus between art and criminal enterprise. The event underscores the dramatic interplay between art, value, and criminal networks. Far from being a relic of history, art crime remains a thriving global business. The Louvre heist serves as a vivid reminder that behind the walls of the world’s most prestigious institutions, art’s allure can also become its greatest vulnerability. This article explores how the black market in art functions as an economy of illicit exchange and a mirror of society’s obsession with value, beauty, and ownership.

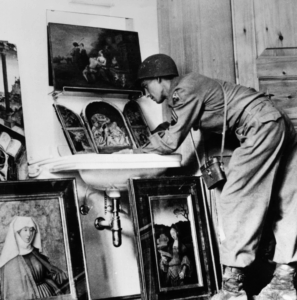

Art theft is often romanticized– the masked thief slipping through laser alarms to steal a masterpiece – but the reality is far more systemic. The Louvre heist demonstrates that modern art crime is not an act of impulsive vandalism but a calculated business model. Most stolen art is never even recovered. The majority vanishes into a global web of intermediaries, collectors, and offshore storage units known as freeports. The 2025 Louvre thieves targeted jewels associated with Napoleon III and the French monarchy, selecting objects that combined monetary value with symbolic power. Such objects are particularly valuable in the black market, where prestige often outweighs liquidity. Once stolen, artifacts may be traded as currency among organized crime groups, such as collateral, or slowly laundered into private collections under false provenance.

This structure echoes a long history of professionalized art theft. A clear parallel can be found in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist (Boston, 1990), when two men disguised as police officers left with thirteen works – including paintings by Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Degas– now valued at over half a billion dollars. Decades later, not a single piece has been recovered. The Gardner case highlights the enduring truth of art crime: it is as much about the symbolic capital of possession as about financial gain. The thieves’ motives remain uncertain, but the gesture of stealing cultural icons continues to haunt the imagination.

While theft removes art from circulation, forgery inserts counterfeits into it, often with equal profit. The black market thrives not only on stealing originals but on producing and selling convincing fakes. The twentieth-century forger Han van Meegeren famously sold “Vermeers” painted by his own hand to Nazi officials, earning both fortune and notoriety. Forgery complicates the very notion of authenticity. If a fake painting produces genuine aesthetic pleasure, is the crime located in the object or in the deception? The black market operates in this moral gray area, where belief itself becomes the commodity. Dealers, auction houses, and collectors sometimes function as intermediaries in laundering illicit art, whether they know it or not. With the rise of advanced imaging, detection has become more sophisticated. Yet, technology has also armed forgers with new tools for reflection. The result is an escalating arms race between art crime and art conservation.

Beyond financial implications, art theft carries immense cultural weight. The Louvre’s stolen jewels, like the Gardner paintings, represent not just property but identity. They are fragments of a nation’s memory. French officials called the 2025 robbery an attack on heritage, language that underscores how cultural artifacts are bound to collective self-understanding. When such items are removed from public view, society loses access to beauty and history. Looted antiquities from conflict zones deepen this crisis. Whether from war-torn Syria or the Balkans during the 1990s, the plunder of art and artifacts often functions as a form of cultural erasure. In this sense, the black market for art is also a market in memory. The black market then trafficks symbols through which civilizations narrate themselves.

The black market in art reveals a paradox at the heart of cultural production: the same qualities that make art valuable (rarity, authenticity, symbolism) make it a target for theft and forgery. The Louvre heist, echoing the Gardner robbery 35 years earlier, exposes the fragility of even the most guarded institutions. In both cases, the allure of art proved stronger than the barriers of law. Art crime is thus a mirror reflecting the contradictions of our cultural values. We celebrate creativity yet commodify it, sanctify art’s uniqueness yet allow its theft to become spectacle. When a masterpiece disappears into the underworld or a forgery hangs undetected, what is stolen is not only the object, but the public’s access to meaning itself. The black market does not just trade in paintings or jewels; it trades in belief.