“You have to decide as a child if you want to ‘pass’ into these spaces by wearing a false machismo or do you want to deal with the social consequences of being yourself.”

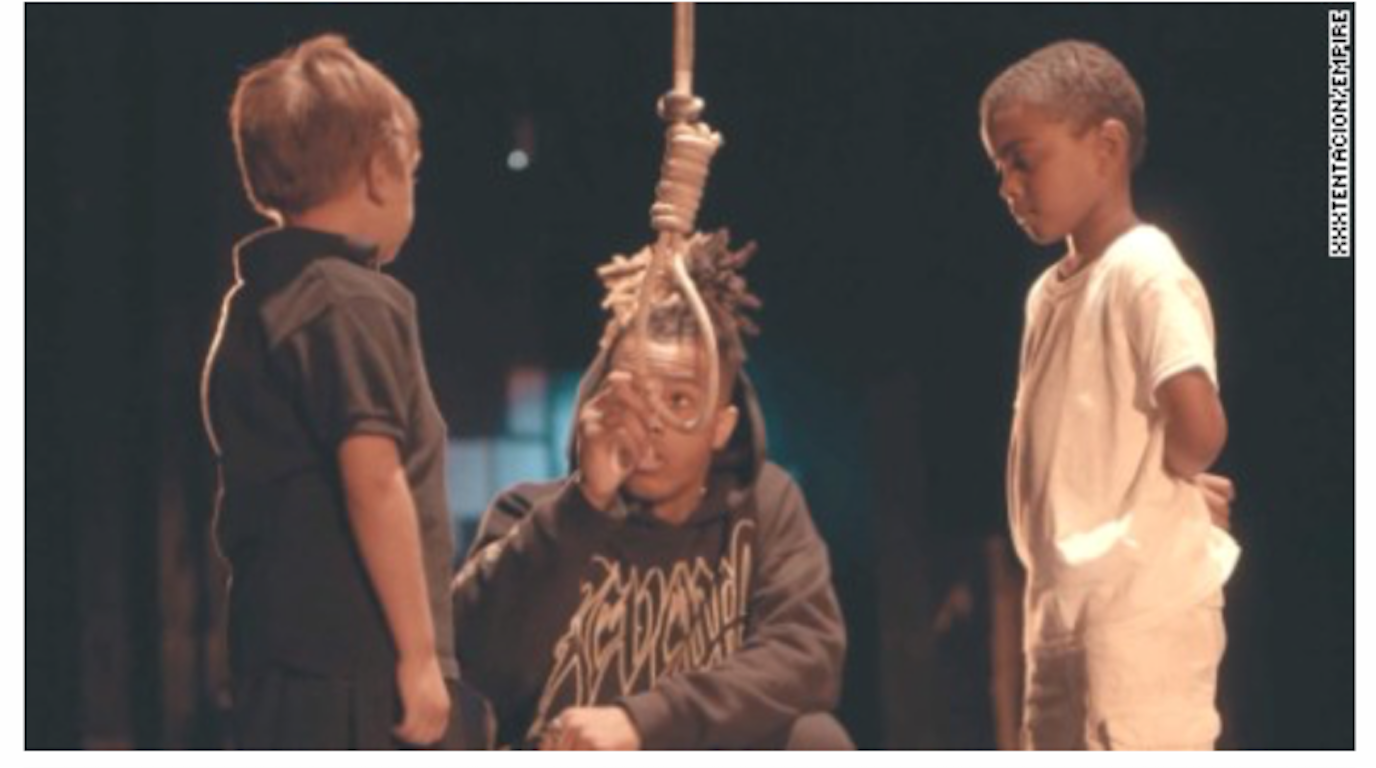

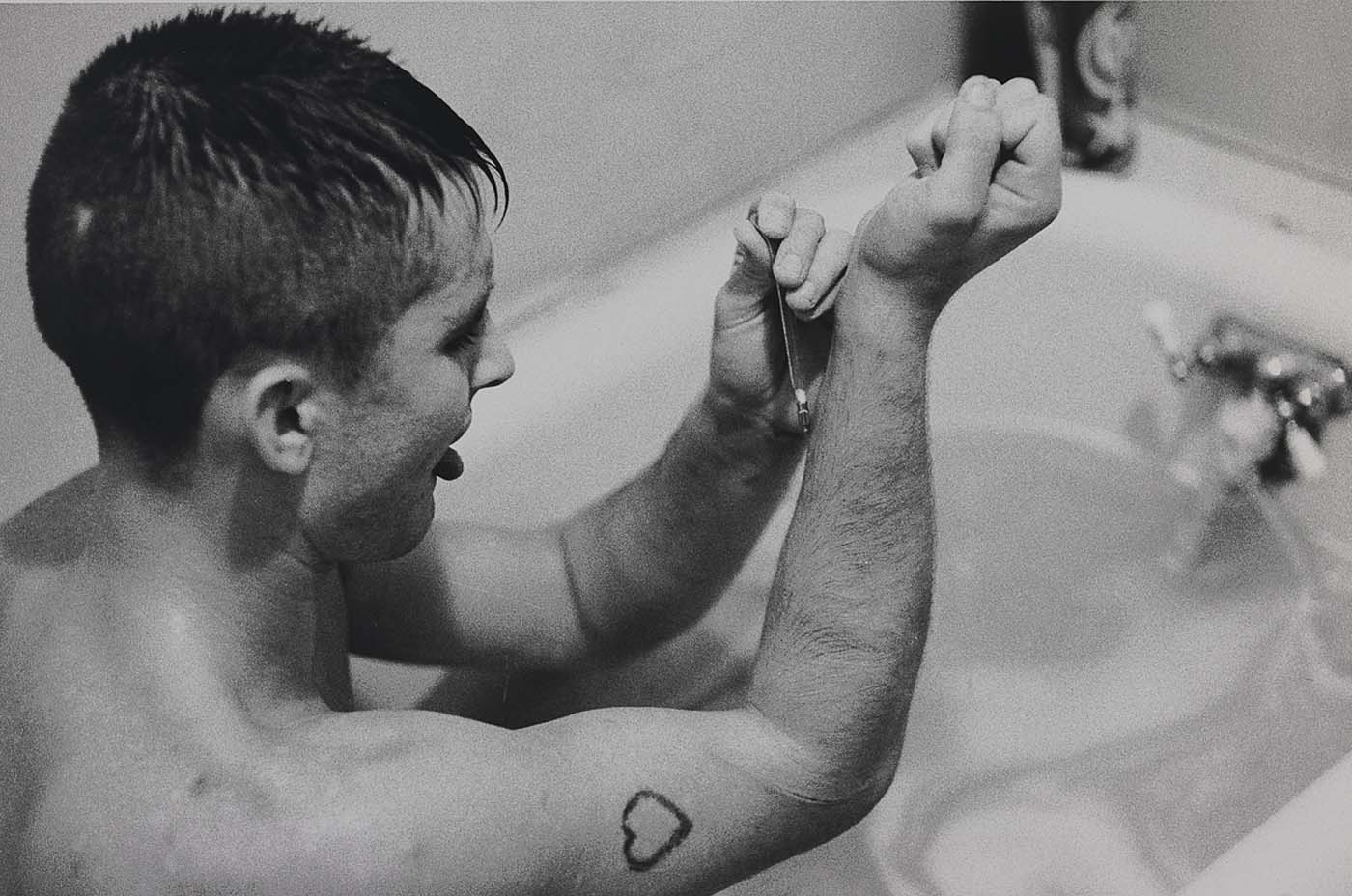

This quote epitomizes the internal conflict children must face when negotiating their own individual self within the scope of social order. The method United States society currently undertakes to raise their youth involves a series of intentional, and unintentional, gendered activities to teach kids their place in the existing social hierarchy. For Shikeith Cathey, this social order was a north Philadelphia neighborhood emphasizing masculine performance from their boys, and the repression of anything feminine or homosexual. As a gay Black man, Shikeith’s photography takes a refreshing step away from this type of toxic masculinity and exploitation of Black men’s stereotypes. Instead, he lets Black men be seen in a gentle and tender light. A light numerous men could be seen in should we allow them to choose from more than just one ‘correct path.’

I think the importance of messages like this cannot be overstated because of how violence in our nation stems from emotions repressed throughout our lifetimes. For the sake of precision, and to keep the topic centered on how toxic masculinity effects men, I will keep the data focused on men’s violence against other men. Michael Kaufman’s article “The Construction of Masculinity and the Triad of Men’s Violence” discussed the ways in which men’s violence is channeled towards other men because of the same avoidance of feeling (otherwise known as femininity) Shikeith mentioned in his community. However, the build-up of emotion without any kind of relief does not negate the emotion itself, the emotion is essentially just ignored until it expresses itself as aggression or violence.

Most men, according to Kaufman, have seen this anger-outlet the same as women have, maybe a rough father who repelled their sons touch. These early encounters with violence aggregate to an anxiety towards other men, all other men could have the potential to humiliate or compete, losing that competition would represent a loss of the power society equates with masculinity. Emotions exchanged between men are framed like they have to be loaded with tension. It is a completely natural sensation to yearn for the love of both parents, but because fathers are taught to suppress emotion, and thus teach their sons the same as they learned, this process is cyclical—unless you are brave like Shikeith.

An example of this tension, is the friendly punch you may give your friend in the hallway at school. Were men to hug one another it would be far too affectionate. Within the culture of male youth, any sign of affection must be balanced with active assault. Another example is the ‘bro-five,’ that kind of hug-slap men do to show that their strength and manliness are not eclipsed by the emotional sentiment they have for the friend. Other socially accepted outlets for this physical affection include muscle building or war or sports, however, there is no model in our society in which erotic love for other males can be safely expressed. Thus, the learned emotional rejection sons receive from their fathers, along with the lack of social avenues male affection can take, ensure homophobia through social learning.

Men are given no method of expressing their love towards other men, and thus they must repress that side of their nature completely. Homophobia is key to maintaining masculinity. To be man, you are not woman. Young boys feel terrified of being a girl because socially girls are inferior to boys, often physically inferior as well. Being a girl is the worst, but being like a girl, is almost as bad. When boys show compassion or “softness” they fundamentally are not being a man, thus, they are like women and must be shunned for breaking the mold. Additionally, homosexual men express the love for their partner that most men have been conditioned to avoid, thus the men giving that love are subject to hatred, even violence in the name of securing masculinity. Ironically though, given the sensual nature of violence—the buildup, the excitement, the release of the act—men enacting violence on gay men in the name of imposing their masculinity, is actually an acknowledgement of their natural attraction towards other men.

Femininity and masculinity are seen as polar opposites on a spectrum of power. Shikeith’s art addresses this binary space in terms of race, his art is not black or white but rather a “gradient of grays” to challenge the social need to categorize and assign people to certain groups. However, his art also comments on this fluidity of sexuality within the spectrum of femininity and masculinity by depicting Black men—arguably an image constantly associated with roughness—in these serene moments.

As breathtakingly beautiful Shikeith’s images are, the shock of seeing Black men in this context would not be a shock at all if we allowed people the freedom to choose their own forms of happiness, rather than imposing a form on them.