In May of 2013, what began as a protest to save a few trees in Istanbul’s Gezi Park erupted into one of the most creative, sarcastic, and art-driven resistance movements of the decade.

In 2013, Turkey was under the long rule of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his AKP party, but tensions had been rising in fears of his increasingly authoritarian-leaning rule. To give some context, when Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002, they were seen as reformers who could bring stability after years of political and economic unrest in Turkey. Early on, Erdoğan introduced economic reforms that reduced debt and boosted growth, and supported democratic reforms tied to Turkey’s bid to join the European Union to expand rights and reduce military power in government. This made him very popular at first, since many believed he was modernizing the country and breaking from the former weak governments. But over time, Erdoğan shifted course. He slowly centralized power, reversed secularism by promoting more conservative Islamic values in public life, and infringed on basic rights. Freedoms of speech and assembly had been shrinking; many journalists were being pressured, and online platforms were frequently censored or blocked. By 2013, many citizens became frustrated, seeing his government as increasingly authoritarian rather than democratic.

Fast forward to the spring of 2013, Erdoğan proposed a plan, the Taksim Square Redevelopment Project, whose aim was to replace Gezi Park with a shopping mall that replicated the Ottoman-era military barracks. This immediately sparked controversy, initiating a peaceful environmental protest to protect one of the few green spaces left in Istanbul. Despite it being a peaceful sit-in, within a few days, the protesters were met with a harsh, violent response from the government. Police used tear gas, water cannons, and forceful eviction of tents; violence that shocked the masses, which spread rapidly through social media. Where mainstream media downplayed or ignored the protests, Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook became essential for spreading information, coordinating efforts, and showing what was really happening. One image in particular, the woman in the red dress being teargassed, became iconic. She was just an ordinary person caught in extraordinary violence. Her image resonated with everyday citizens, calling to others beyond environmentalists. Feminists, secularists, Kurds, LGBTQ activists, and general people angered by political corruption and police brutality joined in because they saw something of themselves in that injustice. That diversity gave the movement a huge cultural force.

Once the confrontation escalated and police brutality became widespread, art stepped in as a means of protest, satire, and identity. Walls, sidewalks, buildings, and public surfaces were covered in graffiti, stencils, and banners. Gas masks, once tools of repression, became the central symbol of resilience and resistance. The AKP’s symbol of the lightbulb was defaced or turned into something new, like a gas mask, symbolizing that the protesters were both rejecting Erdoğan’s narrative and rewriting it in their own frame. Performances by whirling dervishes dancing in gas masks transform religious and cultural symbols into another artistic form of protest.

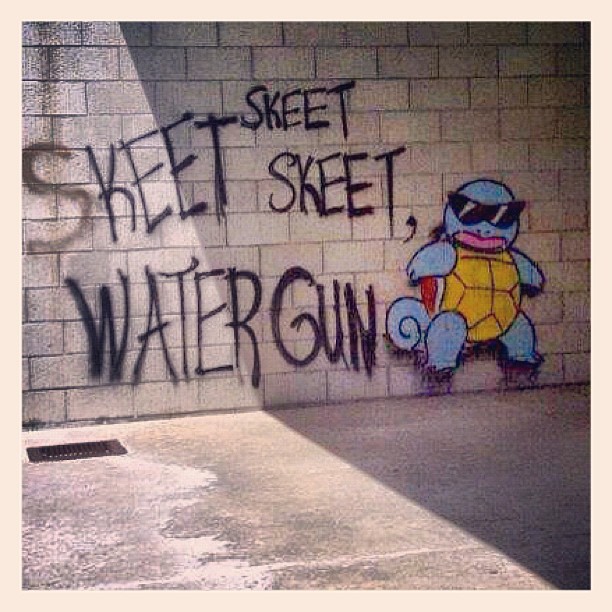

Visual culture became a way to mock and expose the absurdity of government violence. Protesters sprayed sarcastic lines like “Pepper spray beautifies the skin” or “This gas is awesome, dude!” on shop shutters, turning these chemical attacks into sarcastic jokes.

In the beginning, Erdoğan attempted to dismiss the young protestors, giving them insulting names like çapulcu, meaning “looter”, “lowlife”, and “bum.” However, instead of letting the word shame them, protesters embraced it. Teachers and professors proudly marched as “çapulcu professors,” showing that what Erdoğan meant as an insult had instead become a unifying identity across generations. They spray-painted çapulcu everywhere, turned it into memes, slogans, and songs like “I’m sexy and çapulcu,” a parody of the popular LMFAO song “I’m sexy and I know it,” blending pop culture and satire. By embracing and reframing what was meant to be an insult and a tool for oppression, the protestors stripped it of its power and created solidarity through humor.

Graffiti and vandalism, while typically seen as criminal, became necessary forms of expression in a repressive environment. It was through social media and this nuanced form of protest that they drew international attention and exposed police brutality and repression to the world. More than that, the artistic protests showed a different kind of power: the power of humor, creativity, beauty, and symbolism to contrast and challenge authoritarianism. Gezi Park reflects that art is not just decoration, but it can be a tool of resistance and a voice for those who are silenced. What began as a fight for a small patch of green space transformed into a nationwide assertion of identity, rights, and solidarity.