Museums are usually seen as places of learning and culture, places people go to admire history, creativity, and human achievement. But there is a darker side to museums that many people don’t think about. This is the long history of displaying real human beings, oftentimes people of color, colonized people, or marginalized groups as objects. These individuals were treated like artifacts, not humans, and their stories show how institutions that claim to protect culture have also taken part in exploitation. One of the most disturbing examples is Saartjie Baartman, a South African Khoikhoi woman whose body was put on display in European museums for years after her death. Her story reveals how museums can so easily cross ethical lines without batting an eye by turning human lives into something to be looked at rather than respected.

Baartman’s story reveals how institutions often hide harmful practices behind claims of “scientific research” or “public learning”. Taken from South Africa in the early 1800s, she was brought to Europe and displayed in human exhibitions because her body didn’t fit Western norms. Crowds paid to stare at her as if she were some kind of rare creature rather than a real person with a culture, a family, and a life of her own. When she died, things only got worse. Instead of being given a proper burial, her body was dissected, measured, and displayed at the Musee de l’Homme in Paris where her remains stayed in custody for nearly two centuries before being returned to South Africa in 2002 (Parkinson, 2016). For generations, visitors treated her preserved body parts like something to be observed, rather than a human being to be honored. Her story shows that sometimes the biggest crimes aren’t committed by individuals, but by institutions that claim to be protecting culture while actually exploiting it.

And Baartman wasn’t the only one. Museums around the world have stored, studied, and displayed human remains from Native American tribes, Indigenous African communities, Pacific Islander groups, and many others. For example, before the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act passed in 1990, museums in the United States held tens of thousands of Indigenous remains in their collections and according to a 2023 ProPublica investigation, more than 110,000 Native American remains are still held by U.S. institutions today, decades after the law was passed (Jaffe et al, 2023). Many were taken without consent from burial grounds during periods of colonial expansion. These bones and bodies were treated like scientific materials, not like ancestors. Even today, many tribes are still fighting to have those remains returned so they can be properly buried. What’s wild is that museums would never treat the bodies of wealthy or powerful Europeans this way, but when it came to colonized people, the rules were suddenly different.

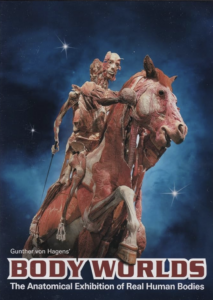

A more recent and controversial example is the “Body Worlds” exhibit. On the surface, it was promoted as an educational art-science crossover as it showed preserved human bodies posed like sculptures. The issue is that there were major questions about whether every donor actually consented. Some investigations even found evidence that some of the bodies may have come from unclaimed corpses in China or even executed prisoners (Harding, 2004). Even if the exhibit taught anatomy, the whole situation still shows how thin the line is between education and exploitation when the “art” is a real human body.

What all of these cases have in common is the simple idea that the museum has the power to decide who is worth human dignity and who is worth putting behind glass. When institutions display human remains, especially from marginalized groups, they send a message about whose stories matter and whose bodies can be used for entertainment or scientific curiosity. It’s basically the museum version of what happens when people turn real tragedy into true crime content, which I touched on in a previous article of mine. Instead of focusing on real human experience, institutions turn individuals into objects that people consume and don’t think twice about.

It’s also important to recognize that there’s a major imbalance of power at play. Museums historically come from colonial systems, where European countries collected or outright stole objects, artifacts, and even bodies from cultures they considered “less civilized.” The fact that Baartman’s remains were displayed for over a century says more about obsession with categorizing and controlling bodies than anything else. If you think about it, turning a person into an exhibit is almost like erasing them. Their real identity disappears, and the museum replaces it with whatever narrative makes sense to them. It’s cultural rewriting disguised as education.

Today, many museums are finally facing pressure to return human remains and rethink how they handle significant cultural artifacts. Some have started working with Indigenous groups, while others have removed displays that were clearly disrespectful. But there’s still a long way to go. Change doesn’t just mean giving back bodies, it also means acknowledging the harm done, rewriting museum labels to tell the truth, and shifting away from the idea that everything “belongs” to museums just because they have it in storage.

A possible solution is stronger international laws that force institutions to get consent, follow cultural protocols, and return remains when requested. Another solution that is not mutually exclusive is transparency. Museums could openly reveal what human remains they still have, how they were obtained, and whether communities have been contacted. Public pressure matters too. When visitors understand the history of exploitation behind certain exhibits, it forces institutions to rethink their choices.

The bottom line is that museums shape culture, and with that comes responsibility. Saartjie Baartman’s story reminds us that behind every display, there is a real human being who deserves dignity. Museums should be places that honor people, not places that profit off their suffering. If cultural institutions want to move forward, they need to treat human remains with the same respect they expect for their most valuable art pieces. Because at the end of the day, the biggest masterpiece anyone leaves behind is their life, which is not something that belongs in a glass case.