Violence towards women, rape culture, and misogyny have been influencing media and art for a very long time. Recently, Maxim Korea released a cover shoot (as seen above) of Kim Byung-Ok, a very famous South Korean actor, standing in back of a car with the trunk open and a pair of bound female legs sticking out. The caption reads: “So girls like bad guys? This is what a bad guy looks like. Dying for him, right?” The editorial following the photo also exhibits disturbing images of what is assumed to be the same woman looking up at her captor, then a photo of her lifeless in the back of the trunk, and later her body in a giant plastic bag.

The release of the cover has been met with outraged backlash. A petition was posted August 26th to keep the issue from the newsstands. The author of the petition, Megal P. states that “Korea has increasing violence crime rate and sex crime rate… Still, Maxim Korea is denying the pain of crime victims, their families, and women who hold everyday fear, putting more weight behind commercial gains and freedom of speech. We strongly demand Maxim Korea to stop selling its September issue and recall what has already been sold. We also plead the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and the Korea Publication Ethics Commission to make a public announcement regarding the issue and come up with measures to stop a next potential case similar to this.”

Maxim’s response was nonetheless defensive: “We did depict the crime of murder and body abandonment in a film noir way, but there’s no hint of a sexual offense in the picture, and no fantasizing of sex crimes either.” So this is not alluding to a sex crime, but a film noir, romanticized murder crime and body abandonment of a woman? Violence towards women is still violence towards women. The woman in the trunk of the car is clearly naked as well—perhaps sexual violence was not directly photographed, but a picture is worth a thousand words. Obviously the photos were staged and taken for artistic purposes, but why is art being confused with pro-violence, misogynistic propaganda? Why are women so often violated and objectified by men they are photographed with for “artistic purposes”? According to Maxim, women like bad boys—no matter what that means for their safety and health.

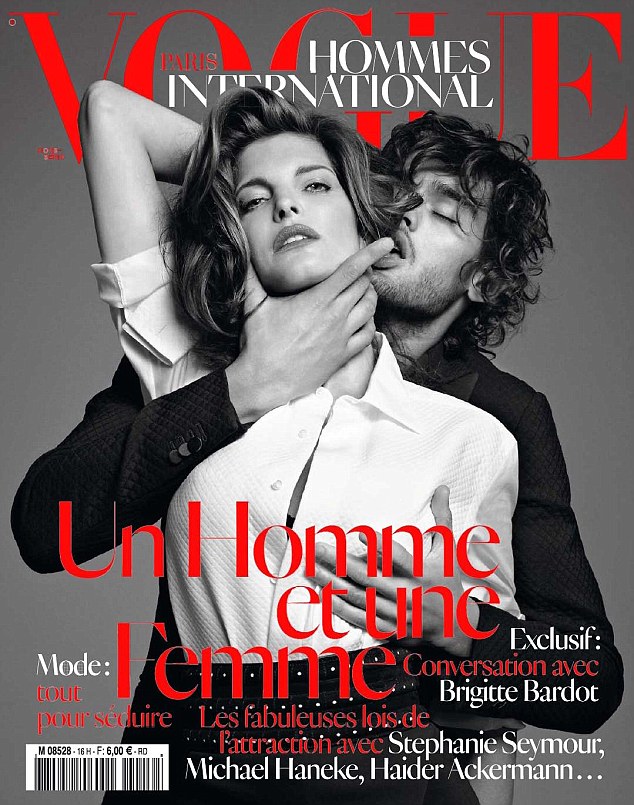

Images of battered women have been on the fashion and advertising scene for years. At first, female objectification and patriarchal dominance was seen in maybe a pose, like a man’s hands softy and passionately around a woman’s neck out of lust. Now, with the help of makeup, costume, and lighting women are no longer lusted after, but murdered by men assumed to be their partners. Often survivors of domestic violence are told by their partners that it is because he loves them so much he cannot help but show it aggressively. Men that are accused and convicted of sexual violence understand women to be property that they must keep under control.

Just last year Vogue Italy released their own magazine spread trivializing domestic violence in a gory, glamourous way. The women depicted in this story posed as high-fashion horror movie victims, screaming helplessly as they’re threatened/murdered by men with different weapons. Vogue Italy claims that the photos bring awareness to domestic violence through a cinematic style, but how can cinema filtered through a fashion editorial not be trivialized?

The biggest difference between Maxim Korea’s shoot and Vogue Italy’s are their subject’s at hand. One parades the smoldering masculinity of violence and the other glamorizes and objectifies the women who suffer because of it. My question is—why is violence excusable and not criminalized when it is displayed as art? Where is the line drawn? Both Maxim and Vogue claim no foul—Vogue even claims it was bringing awareness to the issue—but publishing and distributing violent art enforces the concept as glamourous and cool. When abusive and dysfunctional relationships are romanticized through artistic mediums, it is internalized by impressionable men and women that it is how a relationship should be.

Maybe Maxim and Vogue did have good intentions for the art which they created. One could construe the Maxim cover to be a warning to women that chasing and being with the “bad boy” can be unsafe and might not end on the best terms—for either of them. The Vogue Italy artwork was claimed to “to take action, condemn, and support women in trouble” (vogue.it). Perhaps the two magazines should have utilized their intentions in a more meaningful and powerful way. Would the response to these two articles been as bad if their proceeds were donated to awareness and prevention efforts?

We are unsure the intentions of Maxim’s gruesome artwork (I doubt they will release a statement saying it was to encourage men to be violent so they will be cool), but if it was for benevolent purposes what help is it really? It seems a very elitist concept where attention is brought to an important subject (like domestic violence) by means of extravagant art, and then it is left there with no possible solutions. This kind of art screams, “Hey you! Look at this problem”, but there is no “Let’s fix this together or spread awareness”. This is the same critique I have had towards the interventionist art movement as well. You cannot express the need for a problem to be recognized without giving options or examples for change.

I am left wondering if art is used as an excuse for crime and vice versa. Crime like domestic violence can be displayed in magazines, paintings, and advertisements, yet it is not perceived or treated as a crime because it has an artistic purpose. If the circumstances were vice versa, however, I believe penal action against it can occur. Maxim Korea and Vogue Italy certainly are not the first or last of their kind to draw attention to violence against women/domestic violence in general. However I believe issues like this should not be displayed artistically without action taken to make a real change.

#domesticviolence #fashion #maxim #vogue #advertising