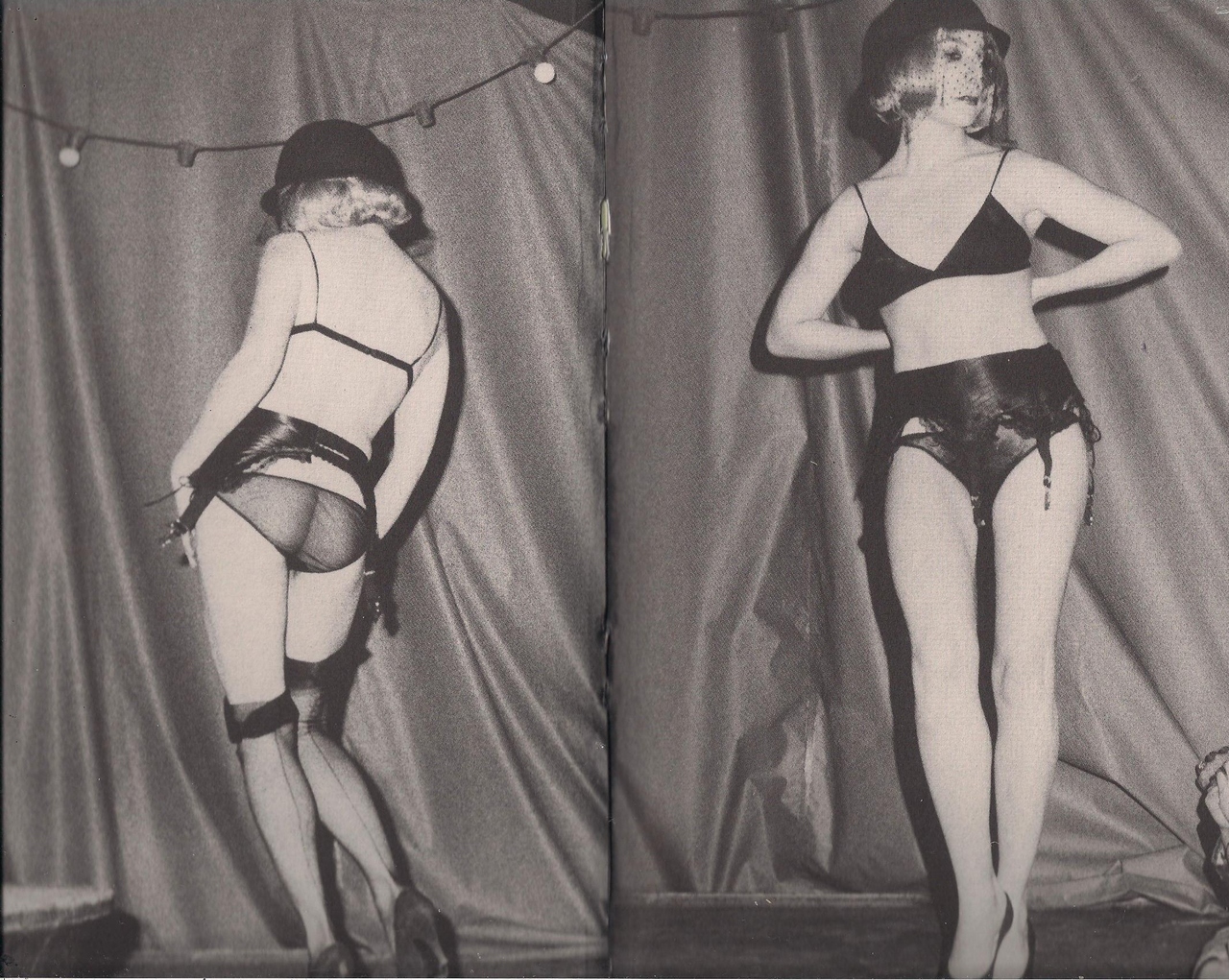

As discussed in class, there is a very fine line between what is considered art and what is considered crime. Often times, it is not clear. An act or piece may fall somewhere along the spectrum, or somewhere within the gray area between the two. Performance art by artists Joe Gibbens and Sophie Calle resides within this gray area. Each of these artists takes something that is generally adjudged as wrong or unconventional—both legally and morally—and blames it on “art”. In other words, their actions are justified by an appeal to artistic expression. Joe Gibbens is a renowned artist, particularly in the field of filmmaking. He is recognized for his innovative autobiographical filmmaking and has created over thirty films. He has belonged to several fellowships and won numerous awards from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Black Maria Film and Video Festival, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Massachusetts Council on the Arts and Humanities. His work has even screened at the Rotterdam Film Festival, the Whitney Biennial, Museum Of Modern Art, the New York Film Festival, and on PBS. Additionally, he formerly taught at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Does Gibbens’ credibility as an artist excuse him from his convicted Capital One Bank robbery in Chinatown this past New Year’s Eve, for which he claims was in the name of “performance art?” According to the state of Manhattan, apparently not. Gibbens was sentenced to one year in prison for committing a third-degree felony robbery, as he had stolen $1,002, all while filming it all on a small, pink and silver video camera. According to Gibbens and other art enthusiasts, his contribution to the cinematic arts made the act worthwhile. Ann Pellegrini, a professor of performance studies at New York University, called the case a classic example of “performance becoming performative,” an act that questions “the relationship between actor, audience and enactment.” The bank teller and the police played roles in Gibben’s art piece unknowingly, making this a criminal act “all in the name of research” as Gibben explains it in “Confessions of a Sociopath”. In February, the Light Industry—a venue for film and electronic art—raised $8,700 with a benefit to support Gibbens during this hard time, and to support the continuation of his artistic contributions. The appeal and excitement of Joe Gibbens’ art is that it skirts the line between transgression and art, permissible by means of research, entertainment, and artistic expression. Joe Gibbons quotes, “I guess in most drama there’s some kind of flaw that drives the drama…but there are aspects that everybody to a greater or lesser degree exhibits, especially the psychopathic ones; people can identify with that. So many movies are made involving these characters.” The takeaway from Gibbon’s comment is that sometimes you have to be a little bit of a psychopath to be an artist and to appreciate art. Sophie Calle is another unconventional artist who got away with morally questionable acts in the name of art. Her book entitled “Suite Vénitienne” and her art piece entitled “The Address Book” involved a considerable amount of stalking. For her book, published in 1979, Calle followed a man she had met at a party to Venice. She called all the hotels until she discovered where he was staying and then convinced a woman who lived across the way to let her photograph him from her window. She also rifled through suitcases and other personal items of hotel guests while working as a chambermaid at a Venetian Hotel and documented it. In 1983, her stalking grew more severe with her artwork “The Address Book”. In this piece, she attempted to use only an address book to produce a portrait of a man she had never met. She found this man’s address book on the street, photocopied the contents, and called and interrogated the contacts, asking them about the book’s owner. She additionally took photographs of other people engaged in his favorite activities. The man, who was a documentary filmmaker named Pierre Baudry, threatened to sue for invasion of privacy when the newspaper Libération published her results. Understandably, this piece was very controversial. In Calle’s other art pieces, she flirted with conventional boundaries regarding intimacy and erotica. Her piece “The Sleepers” is reminiscent of an orgy, as she asked friends and strangers to sleep in a bed together for eight hours. She documented the experience with photographs and by writing down everything the participants had said. The nature of this project, whether it be defined as conceptual art or not, is open-ended, for a man had asked Calle “is this art?” and she had replied, “It could be.” Against her father’s wishes and undoubtedly arousing discomfort amongst its views, Calle’s book “The Striptease” featured photographs of her stripping in a Pigalle club juxtaposed with congratulations cards sent to her parents after her birth. Although not technically considered legal crime, like that of the work of Gibbens, Calle’s artwork involved profanity and moral ambiguity. Perhaps it was in response to the freedom of choice that a late capitalist society endows, for her work often reflected her interest in the interplay between control, compulsion, and freedom. Yet again, we find ourselves pondering if artistic freedom and her thirst for discovery make her morally ambiguous artwork acceptable. Depending on how one looks at it, the acts of these artists could be considered art, crime, or a combination of both. They cause us to ask ourselves this question: does blaming an immoral act or transgression on art make it okay? The answer to this question is equivocal, perplexing, and controversial.